Iron deficiency is a global public health problem. Its function is powerful and so crucial, yet iron is the most common micronutrient deficiency disorder and can significantly impair the health and wellbeing of individuals worldwide. In developed countries, there are specific population groups most at risk. In Aotearoa New Zealand, in a land a plenty rich in beef, lamb and agriculture, iron deficiency is still an issue and rising. In the 2008/09 NZ Adult Nutrition Survey, the prevalence of iron deficiency amongst females aged 15 years and over, increased from 2.9% in 1997 to 7.2% in 2008/09. The Survey also showed that 34.2% of females aged 15-18 years had an inadequate intake of iron, followed by those aged 31-50 years at 15.4%. Iron deficiency is not just isolated to females. As my clients will know, this is a micronutrient I review for both my female and male clients.

So why is this micronutrient so important? Firstly, iron is required to help carry oxygen around the body – and every cell in the body needs oxygen. It is also part of the energy-generating process involved in the body’s chemical reactions that produce energy from food. To ensure a healthy immune system, our body’s cells that fight infection also depend on adequate stores of iron. There are also other complex metabolic processes that involve the role of iron such as in the area of blood glucose management or diabetes and in cholesterol management. So you can see why I am a little iron-pedantic when it comes to reviewing the health of my clients!

Groups that are at risk of iron deficiency include:

- Infants, children and teenagers during their rapid phases of growth

- Women in their reproductive years and during pregnancy

- Those with certain medical conditions such as kidney failure, chronic malabsorption, gastrointestinal disorders and menorrhagia

- People on restrictive or fad diets

- Vegetarians and vegans

- Athletes and very active people who do regular intense exercise.

It is important for each group above to have their considerations to be mindful of. For example, a 7-12 month old infant has a recommended daily intake (RDI) of 11mg of iron – that’s more iron than a grown man (of 8mg)! For women aged 19-50 years, the RDI is 18mg/day and drops down to 8mg/day over the age of 50 years. During pregnancy however, the RDI jumps up to 27mg/day yet a study shows the usual daily median intake of iron in NZ women aged 25-44y was only 10.3mg/day and studies have shown that iron intake during pregnancy had only increased slightly between 11-14mg/day (from food). Athletes also need to be mindful of their iron intake due to tissue growth, increased requirements with production of red blood cells, energy/dietary restrictions and losses through heavy sweating or damage to red blood cells (such as from running on hard surfaces).

There are three stages of iron deficiency where it starts from depletion in our iron stores through to the point where they can become severely depleted that we do not have enough in circulation and it affects the production of our red blood cells.

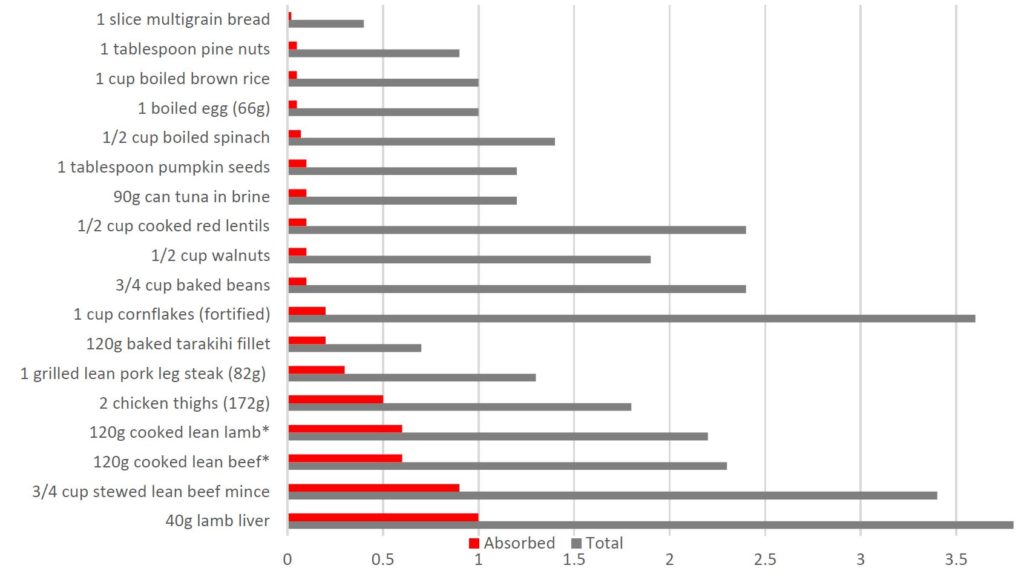

When asked to think of the highest source of iron in food, we often think of red meat. This is true (as well as offal!). Iron found in red meat, fish and poultry are called haem iron – where the iron is originally contained in the haemoglobin (red blood cells) and myoglobin (muscle cells) of these foods. The absorption of iron from these foods is around 15-25 percent. Other sources of iron from plant foods, beans and lentils are called non-haem iron. The bioavailability of these foods however, is significantly lower, at 5-12 percent. When we look at ‘bioavailability’, this is about how much of the iron from food we eat can be absorbed. The absorption of non-haem iron can be variable, based on the body’s physiological requirements, the iron status of the individual and the component of the meal itself – whereas the absorption of haem iron is relatively constant. This is not to say that vegetarians or vegans cannot meet their iron intake through plant foods alone – it just means they need to be much more cautious and aware of their iron intake and ensure they have a varied diet.

For flexitarians and pescatarians, there is a particular MFP (meat, fish, poultry) factor that helps the absorption of non-haem iron. This particular enhancing factor helps the absorption of non-haem iron sources better than if the vegetables were eaten alone. Vitamin C also enhances absorption and this can be easily done by adding freshly chopped parsley or squeezing fresh lemon juice on top to finish off a meal. Just as there are ‘promoters’, there are also ‘inhibitors’. For example, the iron absorption from a non-haem containing meal may be doubled if the meal is taken with a glass of orange juice (containing 30mg of vitamin C) or reduced to a third if the meal is followed by a cup of tea (due to the tannin)! Other iron inhibitors include calcium, zinc, polyphenols and phytates.

Whichever life-stage you or your loved one may be at, or whether you are going through certain lifestyle changes or facing particular health issues, it is important to be mindful of iron. Men and post-menopausal are at low risk of iron deficiency in general, but it can certainly be variable due to all the factors noted above.